Contact: Leah Barbour

Photo by: Alan Cressler

STARKVILLE, Miss.--A pictograph that remained in the dark for almost 6,000 years has come to light with the help of a Mississippi State anthropologist.

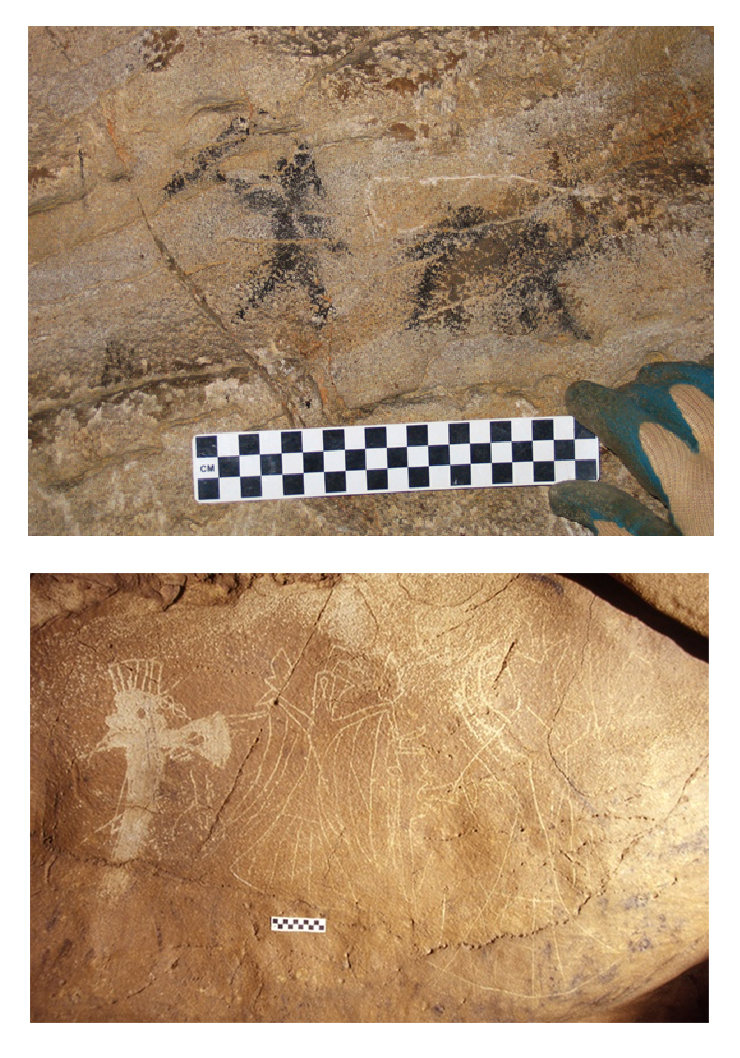

Featuring what appears to be a human hunting, the image -- certainly the oldest ever discovered in Tennessee and among the oldest yet found in America -- is providing new insights into prehistoric life, according to Nicholas Herrmann, MSU associate professor of anthropology and Middle Eastern cultures.

He and a research team led by Jan F. Simek, president emeritus of the University of Tennessee system and distinguished professor of science, have worked for more than a decade in the Volunteer State's Cumberland Plateau. The researchers have discovered numerous drawings -- pictographs -- and etchings -- petroglyphs -- both inside caves and on escarpments. Some of the sites are located at Sewanee: The University of the South, where team member Sarah C. Sherwood, assistant professor, is the school's archaeologist.

The researchers' work has culminated in two recent journal publications.

In Antiquity, they discuss how cave art and open-air rock art provide numerous insights on Southeastern cosmology. They also suggest new research questions.

In American Indian Rock Art, they demonstrate how looted sites still can offer researchers valuable information about history.

"Mapping has been my primary role on the site level and regional level," Herrmann said. "I've been working on detailed GIS (geographic information systems) mapping and then compiling those into a database."

Herrmann said diagramming the sites provided important insights because the team determined that the locations of the open air and cave rock art sites are not randomly distributed, which is discussed in the Antiquity article, "Sacred landscapes of the south-eastern USA: prehistoric rock and cave art in Tennessee."

In fact, mapping revealed that open-air rock art is stacked above the cave art.

"The open-air rock art is not directly above, but as you work down the escarpment, and it becomes favorable for cave formation. There are different types of drawings created in the caves," Herrmann explained.

The open-air sites feature what researchers term "upper world imagery," signified by the use of red ink signifying life and renewal. On the other hand, cave art seems to indicate "lower world imagery" and involves the use of black, a color correlated with death.

Herrmann said the team has concluded that the people who created the drawings chose the location on which to develop their art based on their cosmological principles.

He emphasized that the topic of the second journal article, "You Can't Take It (All) With You: Rock Art and Looting on the Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee," is important not just for researchers, but for the general public, as well.

"We have a big problem in the Southeast caves and rock shelters: people go and loot them," Herrmann said. "They are being bombarded by looters, so a lot of the contextual data is being lost. But, we can't simply write those sites off and ignore them; there's still important data to be gleaned even if they are disturbed."

As Herrmann and his team consider their next research steps, they plan to continue studying the Southern part of the Cumberland Plateau, especially in Sewanee's 13,000-acre preserve.

"We're going to get a much better handle on how the Cumberland Plateau has been used through time," Herrmann said. "These pictographs and petroglyphs are giving us an idea of who was living there."

He and his team also plan to release another article -- accompanied by a detailed map -- that focuses on a single cave they've been studying in Missouri. Cave features there contain very similar iconography to the art the group studied on the Cumberland Plateau.

For more about MSU's anthropology and Middle Eastern cultures department, visit www.amec.msstate.edu.