Contact: Vanessa Beeson

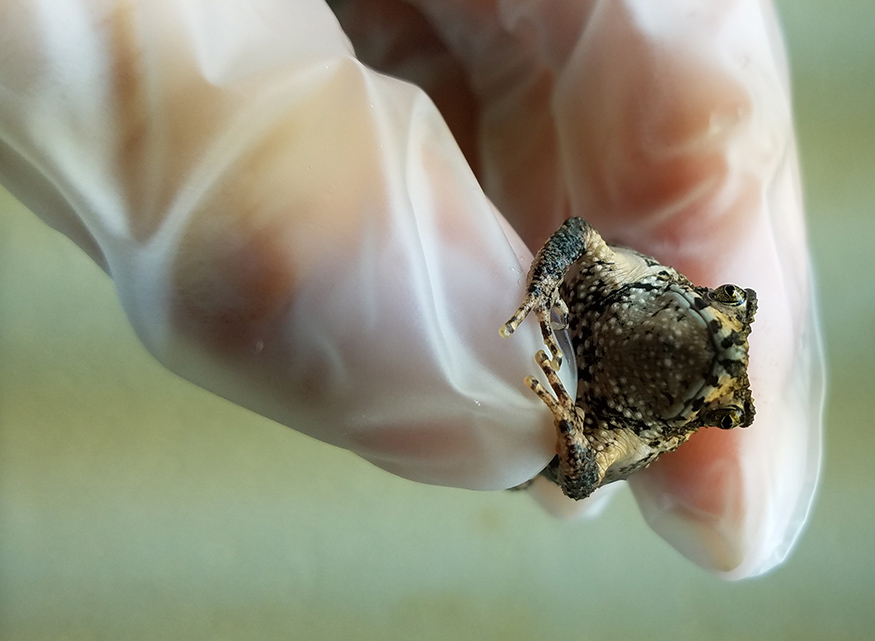

STARKVILLE, Miss.—A Mississippi State University partnership with the Fort Worth Zoo has hatched the first of more than 30 metamorphosed toadlets produced through in vitro fertilization.

A Puerto Rican crested toad named Olaf, hatched at the Fort Worth Zoo this year, is what one might call a work of art. ART, or assisted reproductive technologies, developed by scientists in the university’s Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station and the Forest and Wildlife Research Center, helps amphibians like the Puerto Rican crested toad, considered a threatened species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The technologies include hormone therapies, sperm cryopreservation and in vitro fertilization. MSU also is home to the country’s only National Amphibian Genome Bank, a repository of cryopreserved sperm from approximately 10 of the world’s most threatened and endangered amphibian species.

Carrie Vance, assistant research professor in the Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology and Plant Pathology who co-leads the project, said Olaf is an example of how ART helps increase the genetic diversity and sustainability of populations of threatened amphibians.

“Olaf represents the first time we used cryopreserved sperm from a wild Puerto Rican crested toad as a new genetic line to be combined with an egg from a captive female,” said Vance, who also is a MAFES scientist at MSU. “What’s more is that both of Olaf’s parents have since died of natural causes so Olaf is truly the last of this particular genetic line.”

Vance pointed out that while cryopreserving sperm from wild males, researchers have been able to use hormone therapies to assist breeding. As opposed to other methods, this technique enables researchers to collect sperm without killing the animal, which Vance believes will result in a wider adoption of the practice.

“Previously to introduce genetics from wild individuals into a captive population, the animals were brought into captivity, then paired, and often would never breed anyway. If the collection of sperm from testes macerates was needed, it would require the animal be euthanized,” Vance said. “This new method means we can collect the sperm and release the specimen back into the wild.”

Vance said ART is one facet of a larger species survival plan, which includes steps such as habitat restoration, disease control and establishing an assurance colony in captivity.

“ART helps when amphibians have difficulty breeding in captivity. Typically, amphibian breeding is cued by environmental factors such as day length, rainfall and temperature, which are things that can be difficult to control in a 10-gallon aquarium. When they don’t breed, the genetic lines are lost, and a zoo’s entire assurance colony can collapse.”

Vance said it comes down to overriding the environmental cues and synchronizing the timing of the actual breeding, noting that while it takes males only hours to generate sperm, it can take weeks for females to produce eggs.

“The hormone therapy overrides the environmental factors to trigger the production of reproductive hormones, which cause sperm and egg release. Sperm cryopreservation holds the sperm in perpetuity until the eggs are ready for synchronization.”

Vance has partnered with Andy Kouba, professor and head of the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture in MSU’s College of Forest Resources and scientist in the Forest and Wildlife Research Center, for more than 20 years developing innovative reproductive technologies for threatened and endangered species.

The researchers also have applied ART to the Mississippi gopher frog, considered one of the most endangered in the U.S. Their pioneering work resulted in thousands of Mississippi gopher frogs being produced by zoos around the country and reintroduced into their native habitat.

“Many of the techniques we use on species like the Puerto Rican crested toad were developed using the Mississippi gopher frog,” Kouba said. “The Mississippi gopher frog was the first endangered species ever produced from frozen sperm. The offspring are still alive and have subsequently produced a second generation of offspring, considered another first of its kind.”

Kouba said seeing the applied conservation in action and being able to reintroduce animals back into the wild is what excites him most about the work.

“Globally, it is estimated that 30-40 percent of amphibians are threatened with extinction. In the U.S. that number is closer to 50 percent,” Kouba said. “Our assisted reproductive technologies have led to millions of tadpoles from threatened and endangered species being released into the wild across many species.”

Kouba added that amphibians serve as indicator species for the health of their surrounding ecosystems.

“They are the canary in the coal mine,” Kouba said. “Anything happening in the environment soaks through their permeable skin. Also, they have two life stages, an early aquatic stage and a terrestrial stage, which lets scientists know what is happening in two different environments. As an indicator species, it is important to understand why amphibian populations are disappearing and to try and help the populations recover.”

Support for the Olaf project includes funding from Disney’s Conservation Endowment Fund and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Longtime funding partner, the Institute of Museums and Library Services, supported the early development of this work and currently sponsors the lab’s salamander research. Morris Animal Foundation also has provided previous financial support.

For more on the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, visit www.mafes.msstate.edu. For more on the Forest and Wildlife Research Center, visit www.fwrc.msstate.edu.

MSU is Mississippi’s leading university, available online at www.msstate.edu.