Contact: Leah Barbour

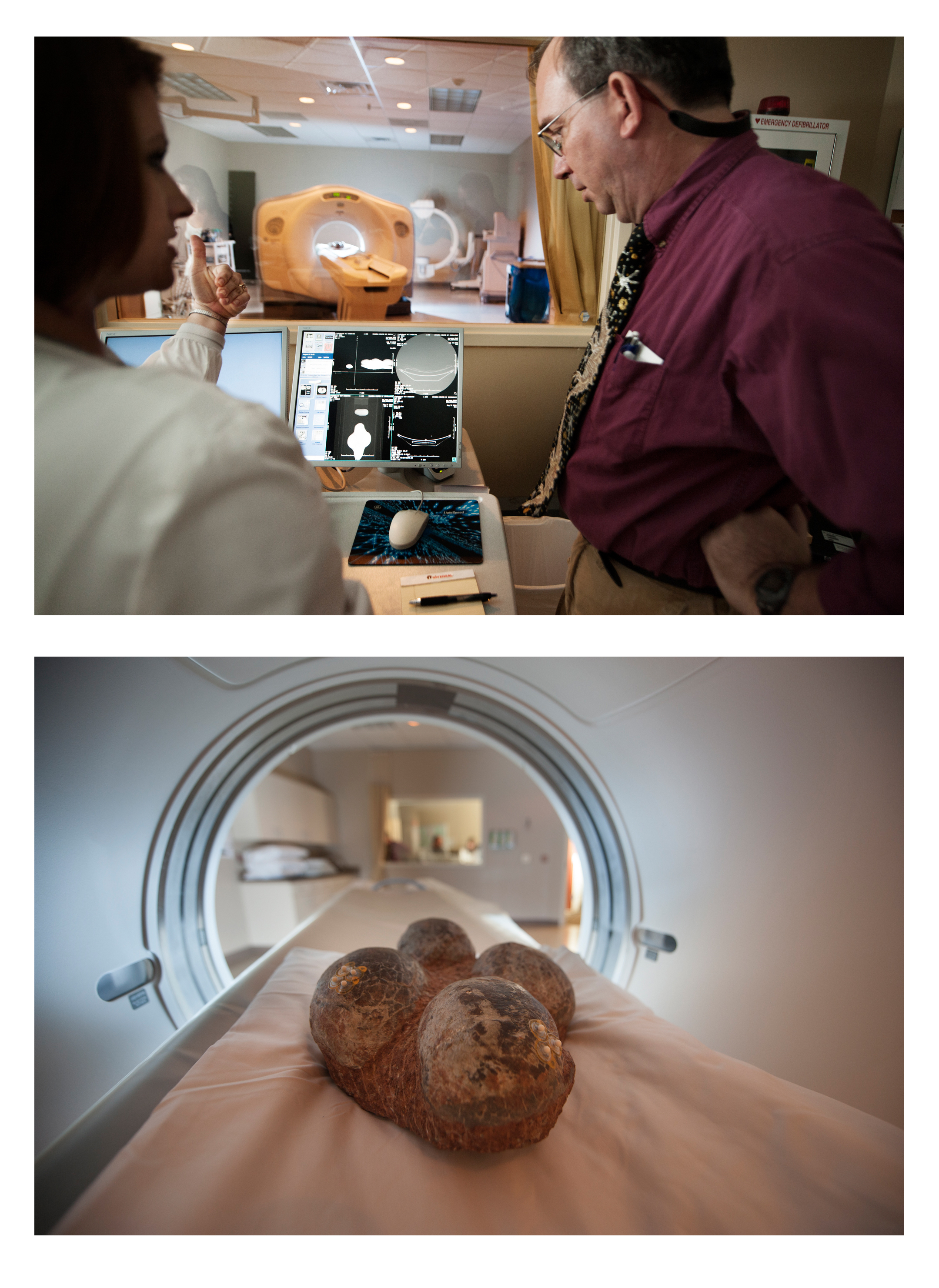

Bottom: Four fossilized dinosaur eggs, part of a clutch found approximately one decade ago by MSU doctoral degree candidate John Paul Jones, imaged by a high-resolution CT Scanner, a research tool available because of a partnership between the university's Institute for Imaging & Analytical Technology and Premier Imaging of Starkville.

Photo by: Megan Bean

STARKVILLE, Miss.--The dinosaur laid her eggs in well-ordered rows on the high ground adjacent to the river while volcanoes exploded in the distance and ash wafted in the breeze.

The herbivorous hadrosaur could not know the river would flood and her clutch would be buried in river sand and volcanic ash for the next 65 to 70 million years.

The eggs that weren't crushed or swept away hardened into fossils. In 2002, John Paul Jones found a clutch with four dinosaur eggs fused to a stone that was once soil.

During the next 10 years, Jones' desire to answer questions about the eggs took him to Mississippi State University, where the geosciences doctoral degree candidate continues his quest.

The eggs, part of Jones' personal collection, are on display each Tuesday from 9 a.m. until 11 a.m. at the Dunn-Seiler Geology Museum, located at the main entrance of Hilbun Hall. Jones, also a graduate assistant lecturer, said he wants to answer visitors' questions and show them the museum's collections.

Jones noted that the study of the dinosaur eggs fossil ties directly to the mission and purpose of the museum, which is open Tuesdays-Thursdays, 9 a.m.-3 p.m. and Fridays, 9 a.m.-noon. In fact, he hopes to include the dinosaur eggs in his dissertation research, which is focused on how increased public understanding of fossils contributes to geoscience education.

"My fossils tie in with our museum," he explained. "Here we have a lot of fossils -- minerals, rocks, meteorites, volcanic rock and fossils that date back from about 10,000 years ago. We have some fossils that people can touch and handle, and a whole wall on Mississippi."

Because of the eggs' location, size and shape, as well as their position in the nest and other artifacts in the vicinity, Jones decided they are most likely some type of hadrosaur -- duck-billed, social, herbivorous dinosaurs that were among the most common and widespread dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period.

However, which species of hadrosaur is inside the eggs remains Jones' biggest question. The only way to identify it will be to examine a skull, if one remains inside the eggs, he said. But cutting into the fossil is not an option.

"If you cut into them, as so many people have wanted to do, then you've damaged the egg beyond repair. You do get direct access, but you've destroyed the bones," he explained.

Modern 21st century technology, though, is allowing Jones to move closer to seeing what exactly is inside the eggs without damaging the specimens.

MSU geoscientist and professor Brenda Kirkland recently advised Jones to scan the fossil with the LightSpeed VCT 64-Slice CT Scanner, a research tool accessible through a partnership between MSU's Institute for Imaging and Analytical Technologies and Premier Imaging of Starkville. The high resolution CT scanner took thousands of 2D X-rays around a single axis of the dinosaur eggs to generate a 3D image of them.

"This way, you've preserved the egg and as the technology continues to improve, the eggs will still be there without destroying the sample. Plus I get to look at the specimens whole. They are beautiful," Jones said.

In mid-August, a few days before the fall 2012 semester began, Robin Luke, technologist and Premier Health Complex facilities director, scanned the eggs and generated more than 10,000 images. The image data sets are being filtered according to density and may offer Jones the answers he's been waiting for.

"We already confirmed that there was an embryo and parts of an embryo inside. In one of the eggs, it appears that there is a skull, and the shape of that skull may be a great help in identifying the species," Jones said.

While he acknowledged that interpreting the data sets will take time, Jones went on to hypothesize the eggs might be the species parasaurolophus, hadrosaurs with huge hollow crests used to make warning sounds or mating calls. If Jones is correct, the skulls inside the eggs would have crests.

"We've got to look at the higher intensity scans to get through the dense rock," he explained.

Jones' quest to unearth more knowledge about the dinosaur eggs and other fossils is giving him the tools he needs to help others get excited about learning science and history, he said.