Contact: Phil Hearn

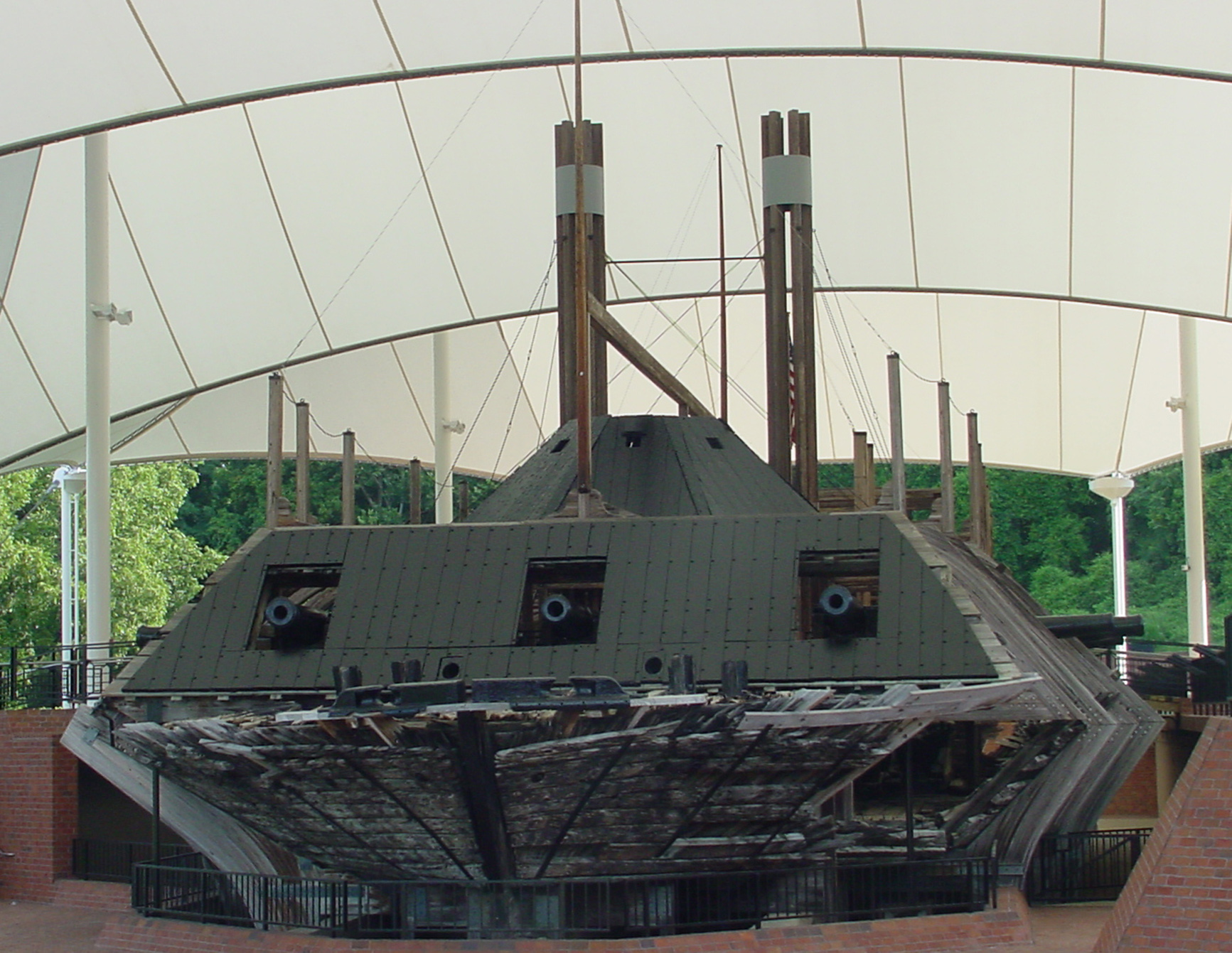

USS Cairo

The USS Cairo's voyage to the bottom of the Yazoo River more than 140 years ago was only the beginning of a battle for survival the resurfaced Civil War gunboat is fighting today against the ravages of time.

In a modern-day struggle to prevent the aged oak vessel's destruction by rain, rust, termites, and birds, the National Park Service is calling on a team of Mississippi State experts who specialize in preventing the deterioration of wood.

"A value cannot be placed on the cooperation and assistance we've received from the university's Forest and Wildlife Research Center," said Vicksburg National Military Park superintendent William O. Nichols. He was referring to the MSU team's 1996 treatment and 2003 re-treatment of the Cairo with a rejuvenating borate-polymer solution.

Confederates who inflicted a Rebel version of hell and high water on the Yankee vessel one cold winter morning long ago, however, may be turning over in their graves.

Attempting to clear enemy mines on the Mississippi River tributary seven miles north of Vicksburg on Dec. 12, 1862, the new Yankee ironclad--it was only a year old--became the first armored warship in history sunk by an electronically detonated torpedo.

Daring federal skipper Thomas O. Selfridge Jr. and his crew escaped with their lives but the Cairo, with gaping holes in both sides of its hull, sank quickly in 36 feet of water. Over the next century, it remained encased in silt and mud.

Built at Mound City, Ill., in 1861, and propelled by two steam engines, the craft was lifted in three sections from its watery grave in 1964 along with its 13 cannon, gun carriages, iron plating and a time capsule of priceless artifacts. It was damaged by cables during the recovery and suffered further deterioration while in storage at Pascagoula.

In 1972, the boat was placed in the hands of the National Park Service, a division of the U.S. Department of the Interior. Five years later, it was towed back to Vicksburg, cleaned and preserved, reassembled and placed on a laminated wood cradle at the battlefield under a canopy that provided partial protection against the elements. With its restoration completed in 1984, the gunboat and its artifacts were placed on public display along a tour road at the USS Cairo Museum.

Since that time, however, the Cairo has continued to be assaulted by wind-blown rains that elude the canopy's protection. Acidic droppings of birds nesting underneath the canopy, poor ventilation, decay fungi, termites, and corroding iron fasteners and other metal parts have further contributed to a degradation of the boat's wooden hull.

Enter a team from Mississippi State that includes longtime forest products professors Terry Amburgey and Mike Barnes, both experts in wood preservation, and research associate Michael Sanders, a Starkville native with a bachelor's degree in industrial technology and a master's in forest products. Sander manages the team's field studies.

As the National Park Service was considering preservation contract proposals that had ranged in the millions of dollars in the mid 1990s, the MSU researchers offered to do the job for $80,000 by simply applying a mixture of sodium borate to control decay and a water-repelling polymer solution. Under a cost-reimbursable contract, they applied a ton of their mixture to the vessel in 1996 at an eventual project cost of only $45,000.

"We took a regular farm tractor and put a regular spray rig on the back of it," explained Amburgey," a New Egypt, N.J., native who joined the MSU faculty 25 years ago. "Then, we hooked garden hoses to the spray rig and we sprayed the entire hull, including the (iron) plating and whatever was there.

"The park service people thought we were nuts when they saw us back up a tractor and start hooking up water hoses," he added.

Amburgey said the borates not only control insects and decay, they reduce corrosion from the fasteners and neutralize the bird droppings by making the wood less acid. The additional polymer solution acts as a repellant against direct water.

Barnes, a Bay Town, Texas, native and MSU faculty member since 1971, said they used a "backpack sprayer to get into the smaller places;" treated the rare, white oak cannon carriages by hand; and caulked a thicker borate-glycol solution directly into drilled holes in structural areas that needed extra strength, such as paddle-wheel supports.

"Whatever you do in a project like this, you don't want to change the boat's historic appearance or texture, and whatever you do should be reversible so that it will not preclude the use of any new technology that may be available 100 years from now," said Amburgey. "We wanted to preserve the historic fabric as it looked, and we did."

In addition to the treatment project, park service officials decided to replace the aging canopy. Unfortunately, while the old covering was being dismantled and the new canopy installed, the vessel spent nearly another year exposed to the weather, which exacerbated the deterioration problems.

So, Amburgey, Barnes and Sanders responded to a new park service call for help this past fall by re-treating the Cairo with another 1,900 pounds of their borate mixture. Utilizing about a half-dozen MSU forest products graduate students working in shifts, as they did in the initial application, they completed the project in four days.

"The knowledge and expertise that professors Amburgey and Barnes have applied in their treatment of the Cairo should enable the National Park Service to preserve this priceless artifact well into the future, for the enjoyment and education of all who visit Vicksburg National Military Park," said Nichols.

For more information on the Cairo project, contact the Vicksburg National Military Park at (601) 636-0583 or the MSU Forest and Wildlife Research Center at (662) 325-2953.