Contact: Maridith Geuder

Played out during the 1990s in news stories, commentaries and movies, the media stereotype of American church burnings portrayed an overwhelmingly rural and Southern crime spree.

A closer look by two Mississippi State social scientists shows the facts don't fully support the myth. Their research recently was published in the journal Rural Sociology.

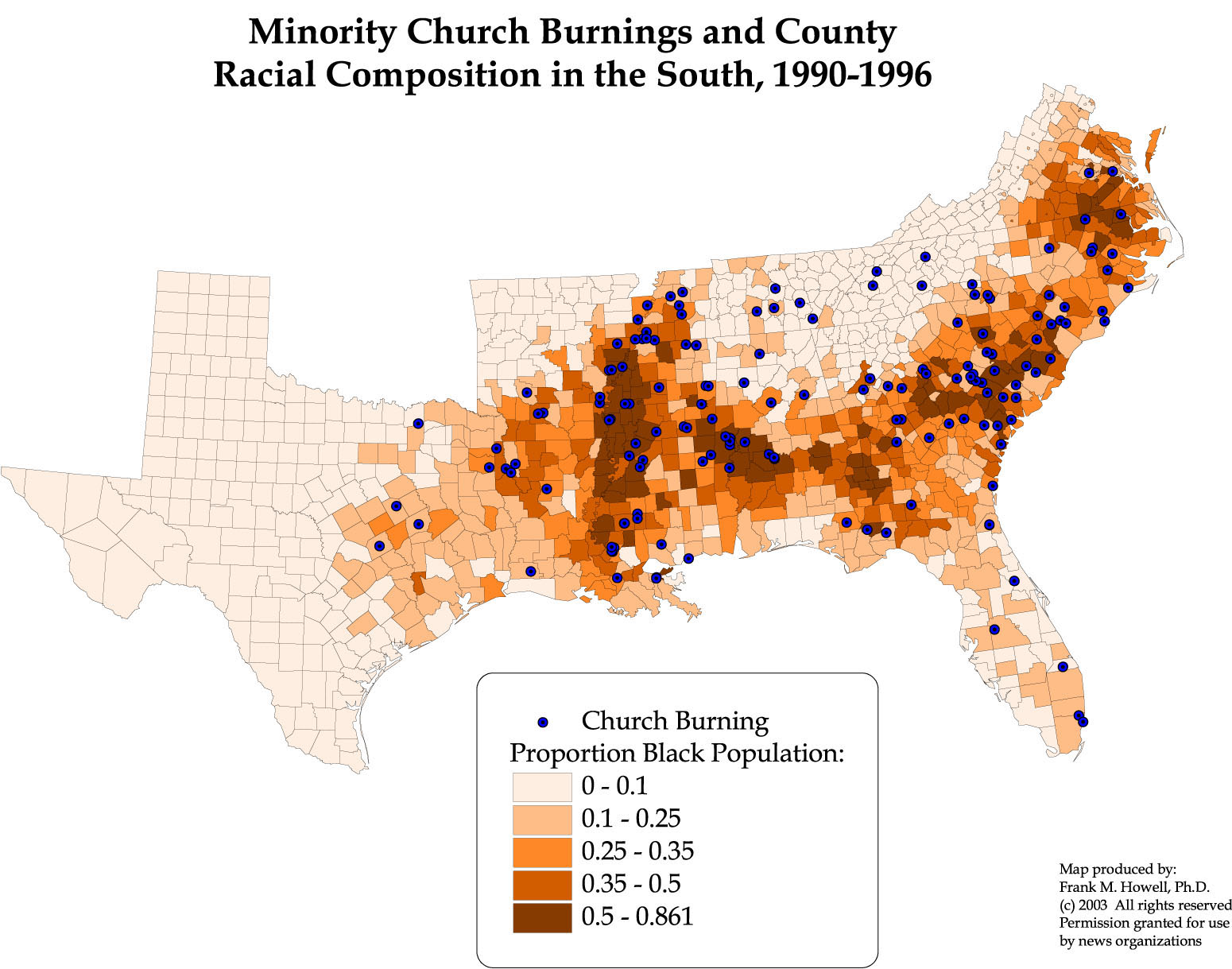

University sociologists Frank M. Howell and John P. Bartkowski used United States Geological Survey data to create maps that show at a glance where church burnings--which rose to more than 200 incidents from 1990 to 1997--predominantly were clustered. Despite stereotypes, they found the problem of racially-motivated church burnings actually to be more urban than rural.

Howell said the project began as a class assignment for his graduate students. "We used a USA Today report as a starting point," he said.

Combining the newspaper's reportage with more extensive data published by the Atlanta-based Center for Democratic Renewal, Howell and former doctoral student Shu-Chuan Lai matched church burning incidents to precise geographic locations on a national map.

In particular, the MSU study sought to determine how the spatial context--community location--and other factors such as racial dynamics and economic inequality influenced church burnings across the South.

Bartkowski said this is the first study to look at the issue on a community level, analyzing social factors such as race, economy, and the relative predominance of religious organizations in areas where burnings occurred.

"We think it's important to evaluate whether there are characteristics that predict the spread of this kind of event, conceived as a hate crime," Bartkowski said. "If, in fact, the phenomenon ebbs and flows, this kind of study can help us determine what kinds of communities are most at risk."

Including a statistical control for the general rate of arson, the MSU researchers determined that the problem, while concentrated in the South, was not the largely rural issue perceived by the public and largely reported so by the media.

Howell said the analysis showed that church burnings began slowly in the early 1990s, with only seven. By 1996, there were 109, with the greater numbers concentrated near larger metropolitan statistical areas. "We discovered two distinct spikes, one in the Dallas area and one in the Aiken, S.C., area," he added.

Howell and Bartkowski said the report's findings should significantly recast an interpretation perpetuated by popular media. "Our findings challenge the idea that this episode of racially-motivated church burnings was solely a rural phenomenon," they write in the journal article.

The study also sought to determine what effect, if any, racial demographics had on church burnings. In reviewing the data, the sociologists discovered that black Baptist congregations had the highest degree of victimization, based on a theory they term an "economy of opportunity."

Bartkowski said the increased number of churches in urban areas "afford arsonists a greater opportunity to burn houses of worship in highly concentrated, circumscribed areas." The large number of Baptist churches in the South would seem to increase the odds, he added.

Combined with a cultural history of civil rights activism, the numerical presence could put such churches at a higher risk for arson. "The pattern of church burnings tended to follow counties where African-Americans comprised higher proportions of the county population," Howell said.

"This is a dramatic phenomenon in the South," Howell said. "Our study is one step toward understanding what happened and what may prevent future incidents. Such research-based analysis is a building block for social progress."

For more information on the study, telephone Howell at (662) 325-7872 or Bartkowski at 325-8621